Are Rising Concerns of Plastic Contamination Leading to New Environmental Regulations?

If it’s plastic, it’s not all fantastic.

The use of plastic plays a large role in our everyday lives – grocery bags, beverage bottles, food wrappers…the list continues. In fact, according to the Natural Resources Defense Council, we produce around 300 million tons of plastic each year worldwide, half of which is for single-use items.

Although single-use items are convenient, many acknowledge how its improper disposal has a direct impact on the environment. However, potential health implications plastics can have on the human body has recently increased public awareness. Similar to the PFAS chemical group, research on the environmental concerns of plastic contamination continues to grow and is monitored by many groups.

What’s the problem with plastic?

Its light weight, strong structure coupled with its low manufacturing costs have fueled the creation of a myriad of consumer and retail plastic products, resulting in the spread of the synthetic material’s use around the world. Built for durability, plastic is largely not biodegradable. In turn, the unfortunate and indiscriminate disposal of plastic products has resulted in the release of large quantities into the environment.

Due to its light weight, plastic litter often 'floats' to the surface making it easily identifiable in bodies of water and roadside swales. Lakes, rivers, swales, and ultimately the ocean itself display plastic debris on their surfaces – a constant visual of the growing environmental problem.

Why not just skim plastic “garbage patches” from bodies of water?

This question points to a larger issue. While discarded plastic debris may start off as macro sized, which are particles visible to the human eye, overtime it does slowly deteriorate. As plastic breaks down from exposure to heat, ultraviolet rays, physical agitation and other weather conditions, it degrades into ever smaller particles. These small particles are called microplastic and often are found with toxic chemicals and bacteria bound on. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), microplastics are less than 0.2 inches (5 millimeters) long1, roughly the lower limit of what the human eye can see. In turn, plastic pollution can release harmful chemicals which pose serious threats to plants, wildlife, aquatic life, and the human population.

For aquatic life, microplastics can be particularly dangerous. Decades of plastic pollution and its degradation has resulted in “vast regions in the ocean where water columns look like a peppery soup because of all the small bits and pieces of plastic”2 which are mistaken for food. Microplastic particles also act as carriers for bacteria and persistent organic pollutants (POPs), which take years to degrade. Consuming both macro-sized and micro-sized plastic itself is harmful to marine animals, but ingesting bacteria-ridden plastic or materials containing POPs could be fatal.1

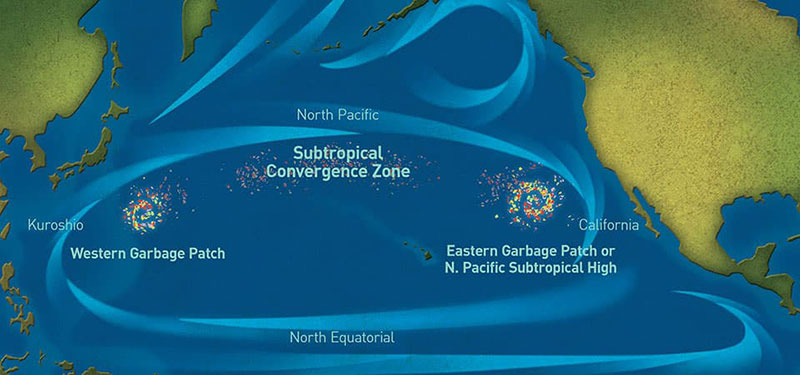

Today, the issue concerning the ultimate fate of plastic in the environment continues to heighten. Scientists have identified large zones of plastic long in the making within each of the five ocean gyres, building on research which discovered the first ‘garbage patch’ in 1997.3

Gyres are semi-permanent, rotating ocean currents that pull debris into one location forming garbage patches. The largest zone is widely referred to as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

Considering how many different types of plastic there are and how each type degrades in its unique way, scientists have started in-depth studies on how even smaller sized, nanoscale plastic particles, may impact human health and the environment. While scientists identify micro-sized particles down to 100 nanometers, nowadays, instruments can routinely measure down to a single nanometer. At this scale particle properties begin to change, can sometimes even adsorb directly through skin, and are considered another defined sized category below the micro-sized plastic particles lower boundary of 100 nanometers.

Where does plastic contamination come from?

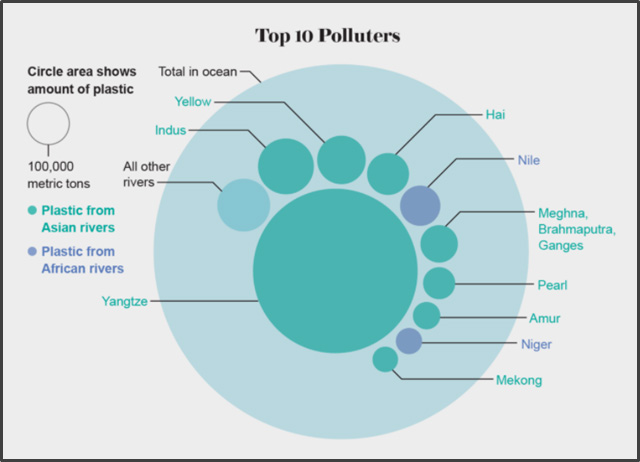

German scientists conducted derivative research on existing studies on 57 of the largest rivers in the world to calculate ocean plastic inputs. Their findings were published and are summarized in the figure below.4

Key takeaways from the publication include:

- The top ten most polluted rivers contribute 93 percent of the plastic entering our oceans.

- The Yangtze, the most polluted river, contributes more plastic into the ocean than all the other world’s rivers combined outside of the top ten.

- Eight of these rivers are located in Asia and the other two are located in Africa.

How are plastic concerns being addressed?

As with all environmental issues, addressing the concern around plastic contamination is complex, yet early steps have been taken. About three decades ago, one early public acknowledgment of the global issue was fast-food giant McDonald’s Corp. 1990 initiative to phase out its foam packaging, including the clamshell hamburger containers.5

An initial step for scientists was defining the problem so accurate data could be collected. Early data in turn helped focus efforts that led to initial steps in addressing some immediate issues such as roadside litter; however, the underlining problem and questions raised by plastic released into the environment continues to be refined. Some pending environmental questions around the issue include:

- What are the sources/types of plastic litter?

- Are certain plastics more toxic than other plastics?

- Where are these sources entering the environment?

- Are there negative effects to the environment’s organism/biota health, beyond the negative visual impacts?

- Are there direct and/or indirect human health issues to consider as POPs bioaccumulate in seafood?

- What options are available to controlling, limiting, or stopping these releases and negative effects?

Together, these questions and the initial steps taken so far are leading to some insight and hopeful progress toward minimizing this highly visible problem.

Where do we go from here?

In California regulatory efforts have begun to emerge to address the needs of policymakers to make informed and effective regulations. Pursuant to State legislation, the California State Water Board has adopted a definition of microplastics in drinking water.

Additionally, the State Water Board is tasked with reviewing existing research to complete the following goals before July 1, 2021:6

- Adopt a standard methodology for testing of microplastics in drinking water;

- Adopt requirements for four years of testing and reporting of microplastics in drinking water, including public disclosure of those results;

- Consider issuing quantitative guidelines (e.g., notification level) to aid consumer interpretations of the testing results, if appropriate;

- Accredit qualified laboratories in California to analyze microplastics in drinking water.

Will the California State Water Board meet its July 1, 2021 deadline?

Interested in learning more about this topic? Be on the lookout for a microplastics white paper in the Environmental Insider fall edition which will continue to discuss the rising concerns of plastic pollution and states’ regulatory steps to address this issue.

_web.jpg?sfvrsn=330347b1_4)

Paul Scian, Senior Loss Control Consultant, Technical Support

Great American Environmental Division

Paul is a Risk Analyst with Great American's Environmental Division. He brings over 30 years of environmental and insurance consulting experience to Great American. Paul's background includes hydrogeology and finance degrees with extensive experience in greenfield, water supply development and brownfield redevelopment. He provides technical support and training to our underwriters and is based out of our New York office.

Resources:

- https://www.4ocean.com/blogs/blog/what-are-microplastics-and-why-you-should-care

- https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/podcast/mar18/nop14-ocean-garbage-patches.html

- https://www.nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/great-pacific-garbage-patch/

- https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/stemming-the-plastic-tide-10-rivers-contribute-most-of-the-plastic-in-the-oceans/

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1990/11/02/mcdonalds-trashing-its-foam-containers/e1ac982a-8058-4308-8d6f-fff1bef20ec5/

- https://www.waterboards.ca.gov/drinking_water/certlic/drinkingwater/microplastics.html