Environmental Insurance Protection: Building on the Past to Handle Both New Regulations and Regulatory Reopeners

The environmental insurance market continues to grow by adopting past best practices to handle new and emerging risks. Working together with diverse practice groups in law, brokerage, engineering, and the sciences; environmental insurance serves a critical client need on property transactions and contractors risks.

Standard industry practices evolve on a wide variety of practice fronts due to the commonality of commercial property transactions between corporate entities. On the environmental front, one of the most common ways corporations protect themselves and others is by conducting a Phase I Environmental Site Assessment.

History of the Phase I

Prior to Congress amending the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA, commonly known as Superfund) in 2002, Phase I studies developed numerous styles in response to the strict, joint and multiple liabilities written into CERCLA when first enacted in 1980. With the lack of standardization, Phase I Site Assessments greatly varied. Some were simple checklists and others followed more detailed approaches. The assessments were offered for both single, one-off transactions and large parties with reoccurring needs.

Standardization of the Phase I Site Assessment came in response to concerns regarding the uncertainty and liability of real estate transactions, particularly those involving brownfield sites. Congress addressed these concerns by requiring the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) to develop acceptable standards for conducting an “All Appropriate Inquiries” (AAI) when dealing with Phase I assessments.

When the USEPA formalized the AAI process of evaluating a property's environmental conditions, the USEPA recognized the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) Standard E1527-XX (XX for last two digits of year issued, first issued as E1527-93, currently E1527-13) as meeting the proper requirements for conducting an AAI. This recognition has led the E1527-13 to become a prominent standard and industry best practice when conducting an environmental due diligence.

Importantly, the USEPA provided that an AAI can provide liability protections for:

“…potential property owners who did not cause or contribute to contamination at the property and can demonstrate compliance with specific provisions outlined in the statute, including conducting AAI into present and past uses of the project…”(1)

For a discussion on how meeting “specific provisions outlined in the AAI statute” may provide a prospective purchaser liability protection, check out Great American Environmental Division’s Lender Protection article.

The difficulty in documenting the prior uses of properties has resulted in a sustained need for both Phase I Site Assessments and environmental insurance on many commercial transactions, both of which continue to evolve to meet the ever-changing needs of business and lenders.

Concurrently, a continued increase and better understanding of chemical compound interactions in humans and the environment has resulted in new and stricter clean-up regulations to address releases into the environment. This includes both historic releases and emerging contaminants of concern as the growing body of environmental knowledge has led to steady, albeit fitful, updates in both the Federal and State environmental regulations.

The following areas demonstrate recent regulatory updates that have resulted from the interaction of USEPA’s AAI guidance, the push and pull between the State and the Federal governments, and society’s increased environmental understanding.

Vapor Intrusion/Indoor Air Quality

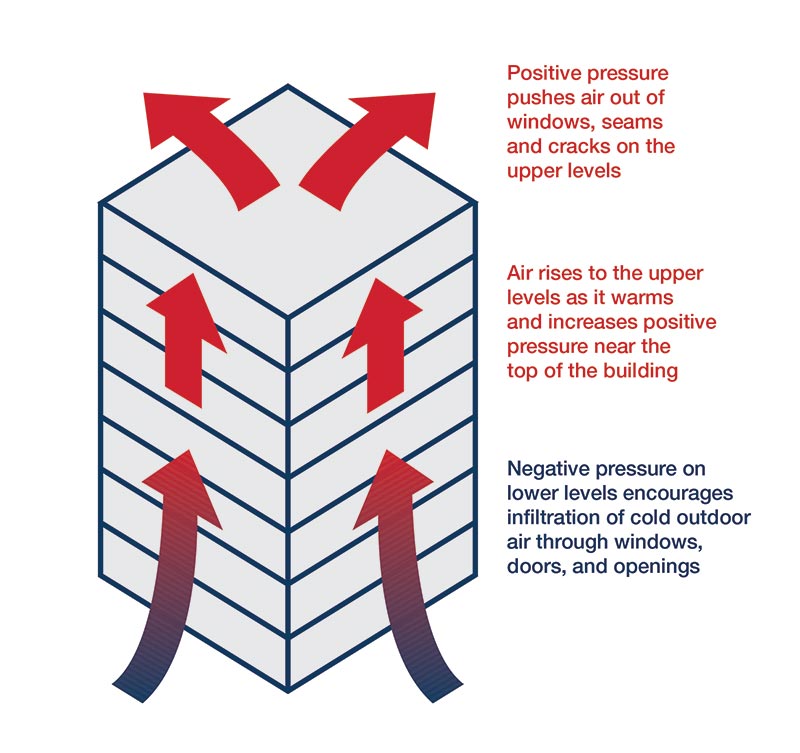

Vapor Intrusion (VI) represents a process in which volatile chemicals in soil or groundwater at a contaminated site migrate as vapor into overlying or nearby buildings indoor air. The risk associated with vapor intrusion (VI) was initially identified in colder areas of the United States due to the heat stack effect in the late 1990s and early 2000s. The heat stack effect refers to the upward movement of heated air in buildings requiring new air to make up for seepage and lost air either from poor insulation, or simply from doors, windows, or chimneys being opened and exposed during the heating season.

Studies found an increasing number of sites where volatile organic compounds (VOCs) entered homes not only directly above a contaminated property but also in surrounding communities, particularly ones down gradient of near-by contaminated sites.

The Redfield site in Denver, Colorado and the IBM site in Endicott New York are examples of where sampling resulted in installation of hundreds of VI mitigation systems at off-site residential properties.

Early VI studies such as these led to widespread changes in VI regulations across the United States. Although the USEPA published an early draft VI guidance, New York lead the nation when the NYS Department of Health provided a VI guidance document in 2006 (2). The USEPA now requires that a VI risk assessment be incorporated into Superfund sites following a 2012 Directive (3). It was recently discovered that the time of sampling related to changing and weather pressure can alter data findings. With this newer understanding, states continue to update VI assessment requirements. For example, California recently updated its VI assessment guidance in January 2019 to reflect these and other new environmental insights.

1,4-dioxane

Previously used as a popular solvent stabilizer, 1, 4-dioxane has been found in studies to be a suspected human carcinogen (4). Many early Superfund sites with chlorinated solvent contamination are now found to also be contaminated with 1,4-dioxane due to its widespread use as a stabilizer.

Although the use of 1,4-dioxane as a stabilizer in chlorinated solvents was largely phased out as a result of the Montreal Protocol and its updates, it is still widely present in many products, often as a by-product of the manufacturing process.

Although it has been on the USEPA’s radar as an emerging contaminant for some time, the USEPA has not established a Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL) for 1,4-dioxane in drinking water. It has only been identified as a health advisory. However, many states have established regulatory clean-up requirements in both groundwater and drinking water. (5)

Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)

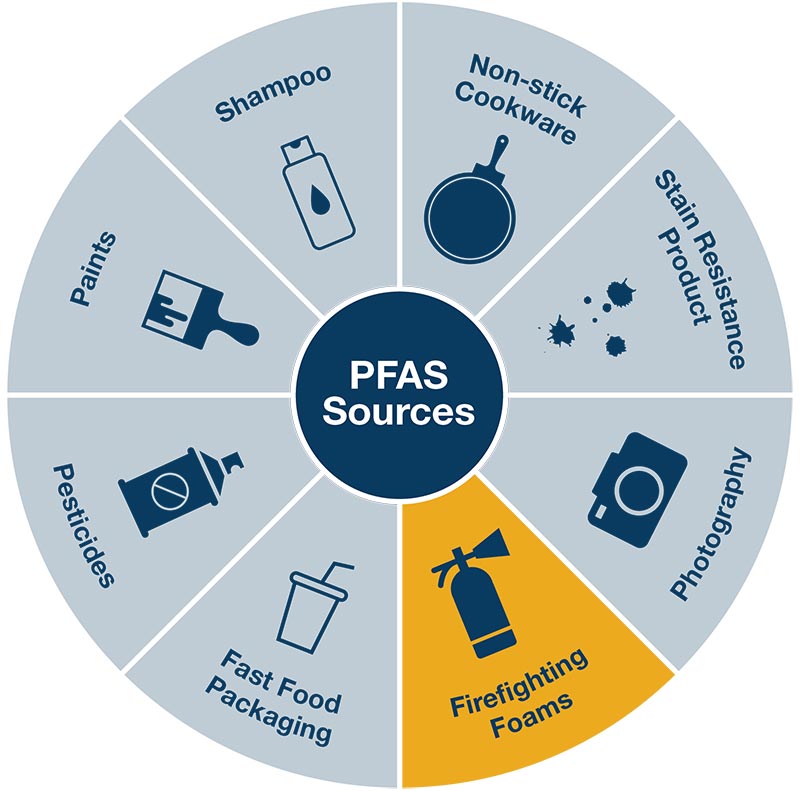

PFAS represents a class of chemicals, which contain thousands of unique formulations, which are combined to make a variety of products. Early formulations have been produced in industrial quantities since the 1940s. Updated PFAS containing firefighting foam, also known as Aqueous Film Forming Foam (AFFF,) were introduced in the 1960s, pushing out earlier non-PFAS versions of AFFF. Today, due to their superior properties and effectiveness in extinguishing large jet fuel fires, PFAS AFFF systems are required by the FAA at commercial airports for firefighting. (6)

Although its traits are useful in many products, in 2007 a study found a troublingly accumulation of PFAS in the blood serum of an estimated 98% of Americans, (7) and that PFAS’ same stable useful traits found in so many products have unfortunately resulted in costly and difficult to remediate releases. The study was the result of a prior epidemiological study showing an association between PFOA exposure, a type of PFAS, and kidney and testicular cancers in individuals who lived near and worked at a plant that produced the chemical (8). These studies have resulted in the removal of longer chain PFAS compounds from the market.

Currently, the USEPA and numerous states have enacted either regulatory clean-up requirements or guidance on this fast-moving environmental concern. Industry consensus suggests that PFOA and PFOS are two of the more toxic, long chained PFAS compounds noted above. Regulatory guidance reflects early efforts to pull these compounds from the market, begin the process of cleaning up releases to the environment, and broadly monitor the chemical class as a whole. Both New York and New Jersey for example now require PFAS sampling at remediation sites, partly in an effort to determine how widespread the problem may be in each state.

A timely, continually updated series of PFAS, PFOA and PFOS facts sheets can be found on the Interstate Technology & Regulatory Council (ITRC). (9)

Environmental Insurance Solutions

New regulations and emerging regulatory exposures contribute to the developing need for environmental insurance protection. As newly identified risks continue to make headlines, existing uncertainties related to prior owner practices on historically developed properties remain a concern. Emerging contaminants are now being addressed with a greater focus and understanding of the importance to document historic site uses. Today’s emerging contaminants soon become yesterday’s clean-up regulation as new risks such as nanomaterials, endocrine disruptors, and more become the focus of emerging studies.

Regulators have made great strides in working with the business community to re-introduce formerly distressed brownfields back to productive uses. The results have generated thousands of jobs and tax income, while also protecting the surrounding community and environment. Environmental insurance can play a vital role in supporting these efforts and those making it happen. Insurance policies can be crafted to address threatening risks surrounding on-site and off-site properties, as well as third parties impacted by emerging exposures and new or historic releases on an insured site.

Environmental liability can be highly complex, but Great American’s dedicated team of experts provide the technical expertise and responsiveness to provide customers with comprehensive insurance solutions.

We invite you to contact us to further discuss how we can best protect your clients!

Want to learn more about environmental contaminants and emerging issues? Check out Sara Brother’s Environmental and Toxic Torts—Claims Management of Emerging Environmental Issues article.

Paul Scian

Paul is a risk analyst with Great American’s Environmental Division. He brings over 30 years of environmental and insurance consulting experience to Great American. Paul’s background includes hydrogeology and finance degrees with extensive experience in greenfield, water supply development and brownfield redevelopment. He provides technical support and training to our underwriters and is based out of our New York office.

References:

- https://www.epa.gov/brownfields/brownfields-all-appropriate-inquiries.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vapor_intrusion.

- https://semspub.epa.gov/work/HQ/176385.pdf

- https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyPDF.cgi/P100THWG.PDF?Dockey=P100THWG.PDF

- https://clu-in.org/contaminantfocus/default.focus/sec/1,4-Dioxane/cat/Policy_and_Guidance/

- https://chemicalwatch.com/71012/us-legislation-to-allow-pfas-alternatives-in-airport-firefighting-foams.

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17438769.

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3855507/.

- https://pfas-1.itrcweb.org/fact-sheets/